On January 19, 2024, The Sequoia Project released draft versions of the Common Agreement and related technical and educational documents related to TEFCA, the Technical Exchange Framework and Common Agreement Project which consumes much of the activity of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). With the certification of the first Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs) in December 2023, the TEFCA network is now operational. One of six “exchange purposes” supported by the network is public health, though only now with the release of the first draft Standard Operating Procedure document for public health can exchange take place without contacting the other party once approved.

On January 19, 2024, The Sequoia Project released draft versions of the Common Agreement and related technical and educational documents related to TEFCA, the Technical Exchange Framework and Common Agreement Project which consumes much of the activity of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). With the certification of the first Qualified Health Information Networks (QHINs) in December 2023, the TEFCA network is now operational. One of six “exchange purposes” supported by the network is public health, though only now with the release of the first draft Standard Operating Procedure document for public health can exchange take place without contacting the other party once approved.

One of the challenges in trying to review these revised documents is that no actual revisions are self-evident; the documents are not distributed with any mark-up from previous documents nor are there any kind of “delta” guides that describe what has changed. There are, however, a series of webinars which should focus on the differences between these proposed and earlier versions.

So what does this mean for public health, now and in the future? We’ll try to answer that by providing some background, and then focusing on the subset of documents that are specifically related to public health.

So what does this mean for public health, now and in the future? We’ll try to answer that by providing some background, and then focusing on the subset of documents that are specifically related to public health.

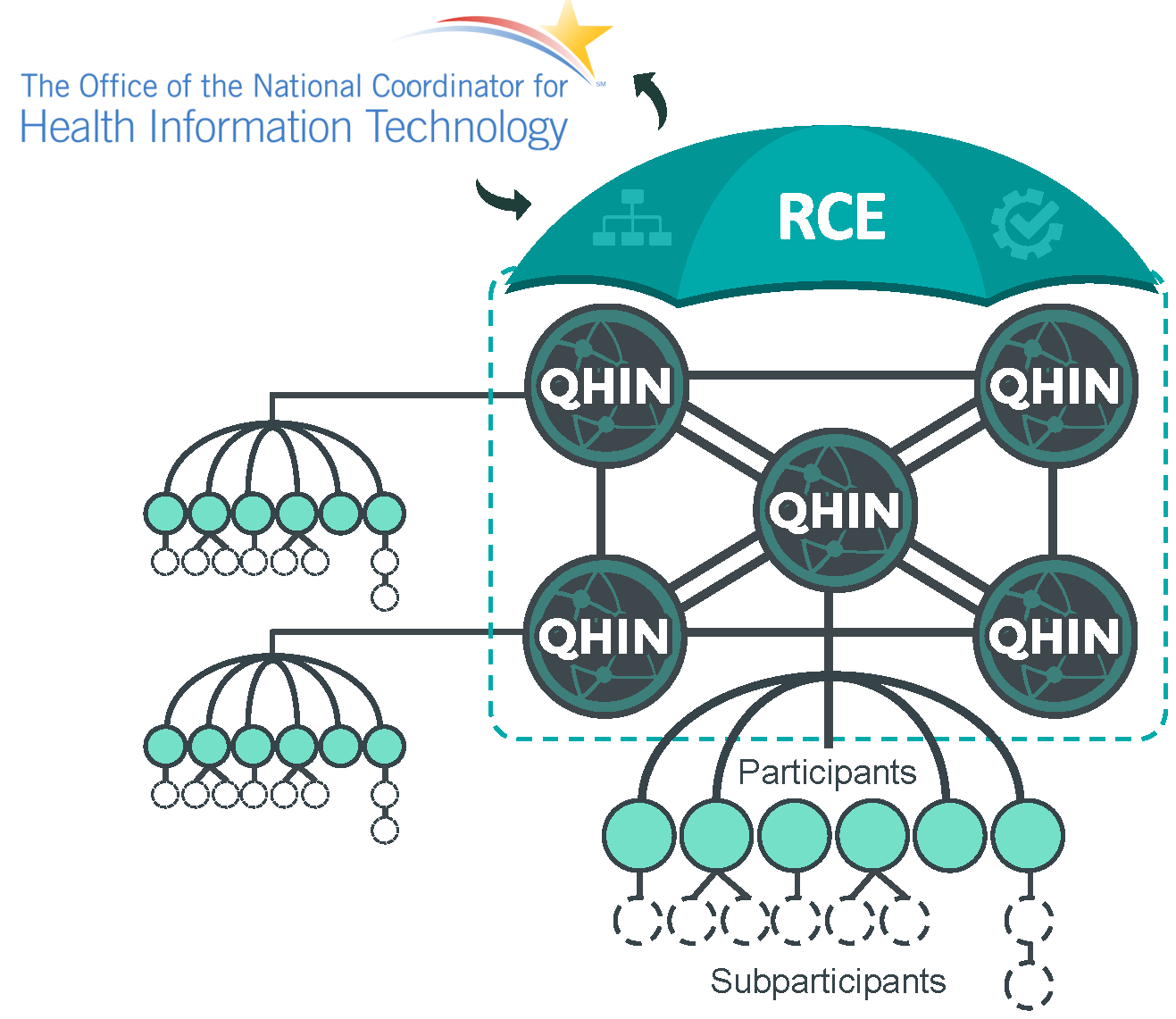

TEFCA is a network of networks: a backbone network that interconnects a small set (likely no more than a dozen) large networks which agree to implement a particular technical architecture (the “TEF” part) abiding by a no-exception data use (common) agreement (the “CA” part) which supports a specific set of exchange purposes. Most healthcare organizations will be TEFCA participants (if they are directly connected to a QHIN) or sub-participants (if they are connected to a participant or sub-participant who is itself connected to a QHIN). Either way, much about what goes on within the TEFCA network will likely happen behind the scenes between QHINs, potentially with little if any operational impact on the actual entities exchanging data at the endpoints (participants and sub-participants). Some participants or users may know explicitly that they are explicitly doing a “TEFCA search” but others may not – their software application may just do the query or submission transparently.

Many of our existing health information exchanges (HIEs) will likely become TEFCA participants by connecting to QHINs and continuing to serve their users (sub-participants) through existing and perhaps new transaction types. Since to be a QHIN an organization must support all the possible exchange purposes, it is unlikely that a public health agency or association (even APHL with its AIMS platform, I suppose) will become QHINs. Their participation in TEFCA will be through participant organizations that will register their network endpoints in the TEFCA resource directory and make them eligible to participate in TEFCA-supported interoperability transactions.

The technical framework (described in the QHIN Technical Framework or QTF document) is an implementation of data exchange standards developed by the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) standards development organization which primarily support two “exchange modalities:” query/response for clinical documents presented using the HL7 Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) and uses SOAP-based web services for transport between end points; and the transport of messages between participants via IHE’s XCDR standard. These standards are primarily used between clinical care organizations to query for patient records to support clinical care; in many cases, existing networks that support these standards, like Carequality, currently only support clinical care. The proposed update to the QTF now adds exchange based on the HL7 Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard to the mix, facilitated by QHINs but still essentially arranged by the participants among themselves.

By and large, public health has stayed away from HL7 CDA, though there are some exceptions like the electronic initial case report (eICR) for electronic case reporting (eCR) and the standard reporting to central cancer registries. But even in these cases, IHE standards and architectures are typically used only with respect to transporting messages and not the core query/response that IHE (and therefore TEFCA) typically supports. To make matters more complicated, TEFCA has a secondary, emerging architecture that supports the newer HL7 FHIR standard, but it will take a little time for this type of interoperability to be fully supported within TEFCA (see our earlier blog on the TEFCA FHIR Roadmap). Likewise, while work is being done to incorporate FHIR into public health interoperability (most notably by the Helios FHIR Accelerator) it will take years for existing public health transactions to migrate to this standard.

How have things changed with these new draft documents? Much of this is described in the draft Public Health Exchange Purpose (XP): Educational Guidance. This guide does a good job of explaining what the major pieces and parts of TEFCA are all about, and what both the policy and technical frameworks are for its implementation and use. It identifies the initial use case that will be supported in the public health exchange purpose (case reporting and case investigation). It makes passing references to some common public health data intermediaries (like the APHL AIMS platform, leveraged for eCR among other things), but does not mention others (like the IZ Gateway for immunization interoperability. These transactions could be supported through existing IHE standards (by attaching an HL7 v2 payload to an IHE-based message) but this type of interoperability is not generally supported by public health agencies who need to receive the data.

For the first time there is a draft Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) document for the public health exchange purpose, which essentially provides the necessary message header and coding information for IHE transactions sent using the TEFCA network only for eCR, electronic lab reporting (ELR), other disease reporting (whatever that means), and electronic case investigation (which refers to the nascent methods for having public health query an electronic health record for additional patient information that is just now being discussed, designed, and tested). Any other public health transactions are not yet permitted (immunization reporting, cancer registry reporting, syndromic surveillance). But remember: aside from some use of IHE XCDR for transport via SOAP web services, these named transactions are rarely if ever executed using IHE protocols and standards. And other public health transactions like immunization reporting are never executed using IHE protocols and standards. And the query/response functionality supported by TEFCA is IHE-based query response for clinical documents which, again, is not typically used by public health.

From a document review standpoint, there is little to which to object from a public health standpoint. The Exchange Purpose (XP) Implementation SOP: Public Health SubXP-1 is fine for what it is; whether it provides any usefulness to public health implementations in the near term is less clear. Acceptance of this SOP will (in practical terms) allow TEFCA to transport eICR-related messages from clinical care organizations to (and from) the Reportable Conditions Knowledge Management System (RCKMS) on the APHL AIMS Platform much as the eHealth Exchange does today. But none of these new documents really explain how/if commonly-used public health data intermediaries like AIMS and the IZ Gateway will be leveraged specifically by TEFCA (albeit those entities need to determine that for themselves), and whether in practical terms public health agencies should plan to do anything differently in the near term. For now, it is prudent for public health to take a “wait and see” posture and see how the TEFCA implementation plays out.

See our other posts about TEFCA.